Values in school Education

What do we know about values

What are values?

Values are broad goals that shape the way we live our lives. To reflect on your own values, simply ask yourself “What matters to me in life?” or “What kind of person do I want to be?”. The answer to questions like these provide insights into your own values and what you believe it means to live a good and meaningful life.

What are the different types of values?

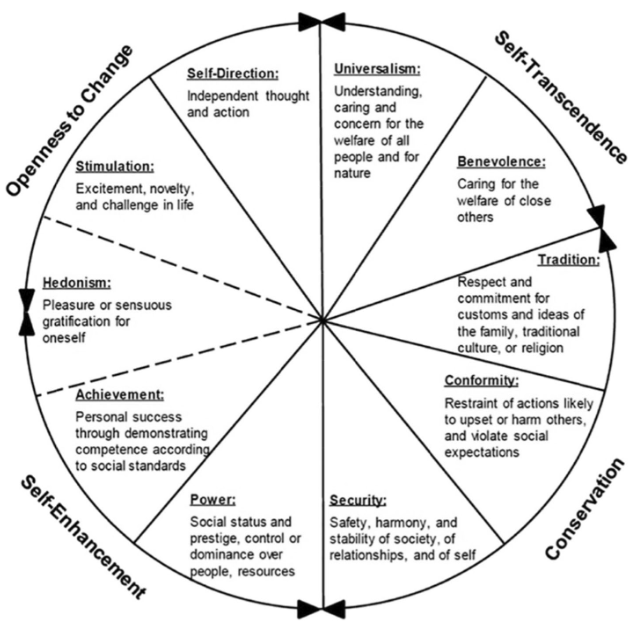

Researchers have found that people around the world share common patterns in the values they hold. Values tend to fall into four different categories: Conservation, Openness to change, Self-enhancement, and Self-transcendence.

For example, some people want to leave things as they are (Conservation), while others look for change in thought and action (Openness to change). Similarly, some people focus on advancing themselves even at the expense of others (Self-enhancement), while others focus on helping close and distant others, including natures (Self-transcendence).

Psychologist Professor Shalom H. Schwartz created the Theory of Basic Human Values to break down these four categories in greater detail. He identified ten key values that drive human behaviour: Universalism, Benevolence, Tradition, Conformity, Security, Power, Achievement, Hedonism, Stimulation, and Self-direction.

How do values relate to one another?

Sometimes different values align closely, meaning that actions in pursuit of one value naturally support the goals of another. For example, people who value achievement usually also value power. Achievement is about striving for personal success and recognition, while power is about attaining leadership positions and elevated social status—goals that often go together.

On the other hand, sometimes values clash because they represent opposing goals. For instance, conformity focuses on the importance of following the rules and meeting social expectations, while self-direction prioritises independence, personal expression, and exploring new ideas. Pursuing one of these values often comes at the expense of the other.

For example, imagine your boss asks you to do something you strongly object to. You can either comply or refuse. Complying fulfils conformity values but conflicts with self-direction values like independence and freedom. Therefore, you are likely to react to this situation based which of the values is most important to you, conformity or self-direction.

Now imagine your boss starts rewarding you more for following the rules than for thinking independently, perhaps with promotions or a higher salary. Over time, you might begin to value conformity more and self-direction less because it benefits you more to conform.

This example shows how our environment can also shape our values. When an environment strongly reinforces one value (like conformity), it can weaken conflicting values (like self-direction). This can lead to unexpected — and unwanted — outcomes (such as creating very obedient workers who don’t think or act independently).

It is important that we understand the dynamics between values, including the potential trade-offs we face when cultivating one type of value over another. This understanding is especially important when we consider the specific values we want to nurture in children and within the classroom environment.

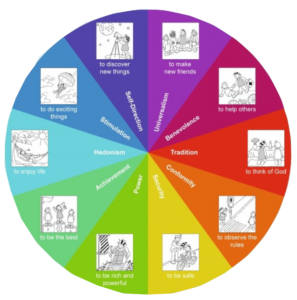

How do values guide behaviour?

Values aren’t just abstract ideas; they’re deeply connected to our emotions and guide the choices we make in life. They give us motivation and meaning, acting as a compass for how we interact with the world and others around us.

For example, if you value caring for friends and family, you might prioritise loyalty and protecting your loved ones. Someone else, who values independence, may focus on exploring new ideas and making decisions for themselves.

When it comes to children’s values, research shows that children who value caring for others are more likely to act fairly and share.

Each person places different levels of importance on the ten basic values, creating a personal “hierarchy of values.” These priorities shape behaviour and decisions.

For instance, someone who highly values stimulation but not conformity might embrace unusual or adventurous activities, like extreme sports.

Our values don’t just shape daily actions—they also influence bigger life choices, like career paths, social causes we support, and even political views.

The picture above displays a circle containing all ten basic values. Using this picture, we can determine which values align and which conflict with each other.

Values placed next to each other in the circle align in their goals and are likely to support similar behaviours. For example, hedonism and stimulation both focus on enjoying life and seeking excitement.

In contrast, values located on opposite sides of the circle are more likely to clash because they represent conflicting priorities. For example, achievement can clash with benevolence, as one focuses on personal success while the other focuses on helping those around us.

Ultimately, our values exist in a state of balance, and by understanding how values interact we can learn how to effectively promote beneficial values in the classroom.

The importance of values in education

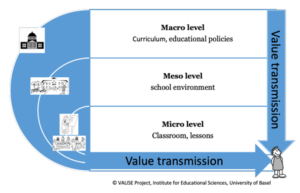

The educational system plays a critical role in shaping the values of children. Values are communicated to children at various levels, including the content of the curriculum (the Macro level), the culture of the school (the Meso level), and the teaching styles of individual educators (the Micro level).

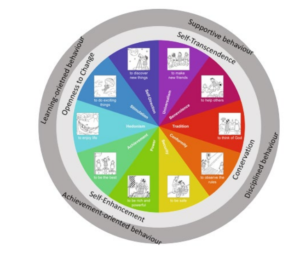

Values influence how students interact with each other, approach challenges, and participate in the learning process. They play a direct role in shaping learning-related behaviours, such as self-discipline and supportive behaviour, as well as motivations like being achievement-oriented or learning-focused.

Recognising how specific values impact the educational process is essential. For example, values such as stimulation and self-direction are closely linked to learning-oriented behaviour in students. This can take the form of intellectual curiosity, creativity, and openness to new ideas—all of which are highly beneficial for learning.

At the same time, it is important to remember that emphasising certain values can unintentionally suppress the opposite values in the circle. For example, placing too much emphasis on conformity and tradition—such as rigidly following rules or adhering to established norms—may discourage intellectual curiosity and independence associated with values like stimulation and self-direction.

Similarly, if the classroom environment focuses too heavily on achievement—rewarding competition and being better than everyone else—values like benevolence and fairness may take a back seat, as children learn to prioritise personal success over helping others.

Therefore, if educators want to promote positive and balanced values in students, it is crucial to deepen our understanding of how these values develop and how schooling influences this process.

The VALISE project, its findings, and resultant advice for educators

The VALISE Project

What is the VALISE project?

The Values in School Education (VALISE) project studied how primary schools may influence children’s values. Conducted between 2020 and 2024 in Switzerland and the UK, the project explored two key questions:

1. How do children’s values change as they grow?

2. What factors in schools may shape their values?

This research helps us understand how schools can promote values that support learning and personal growth.

This website highlights the VALISE project’s main findings and offers practical advice and resources for teachers to bring evidence-based value education into their classrooms.

Findings of the VALISE projects and resultant advice for educators

Oeschger T. P., Makarova E., Daniel E., & Döring A. K. (2024). Value-related educational goals of primary school teachers: a comparative study in two European countries. Frontiers in Psychology.

Döring, A. K., Jones, E., Oeschger T. P., & Makarova, E. (2024). Giving voice to educators: Primary school teachers explain how they promote values to their pupils. European Journal of Psychology of Education.

Oeschger, T. P., Makarova, E., Raman, & Döring, A. K. (2024). The interplay between teachers’ value-related educational goals and their value-related school climate over time. European Journal of Psychology of Education.

Scholz-Kuhn, R., Makarova, E., Bardi, A., & Döring, A. K. (2023). The relationship between young children’s personal values and their teacher-rated behaviors in the classroom. Frontiers in Education.

Oeschger, T. P., Makarova, E., & Döring, A. (2022). Values in the School Curriculum from Teachers’ Perspective: A mixed-methods Study. International Journal of Educational Research Open.

Scholz-Kuhn, R., & Oeschger, T. P. (2022). Project Report 1. (The Formation of Children’s Values in School: A Study on Value Development Among Primary School Children in Switzerland and the United Kingdom) Institut für Bildungswissenschaften, Universität Basel.

Stefanie Habermann, Anat Bardi, Anna Döring, Emma Jones and Matthias Steinmann – VALISE Project Report 2. (Values in School Preliminary Results of the VALISE Project. Data From the United Kingdom)